Let There Be Light is a collaborative mural project between the Jewish Federation of Cincinnati and ArtWorks, designed by Jessica Tamar Deutsch. As part of the Jewish Cincinnati Bicentennial, this mural is a gift to the city of Cincinnati from the Jewish community. The mural celebrates significant contributions by Jewish Cincinnatians to the city’s growth and development over the past two centuries. Its contemporary design evokes the feeling of a tapestry or ketubah — a binding love letter to the city. Taking viewers on a visual journey through the community’s vibrant past, it showcases landmark institutions and significant contributions of Jewish Cincinnatians. Through the mural, viewers can see joy and legacy, inspiring pride, healing, and connection within the local Jewish community and beyond.

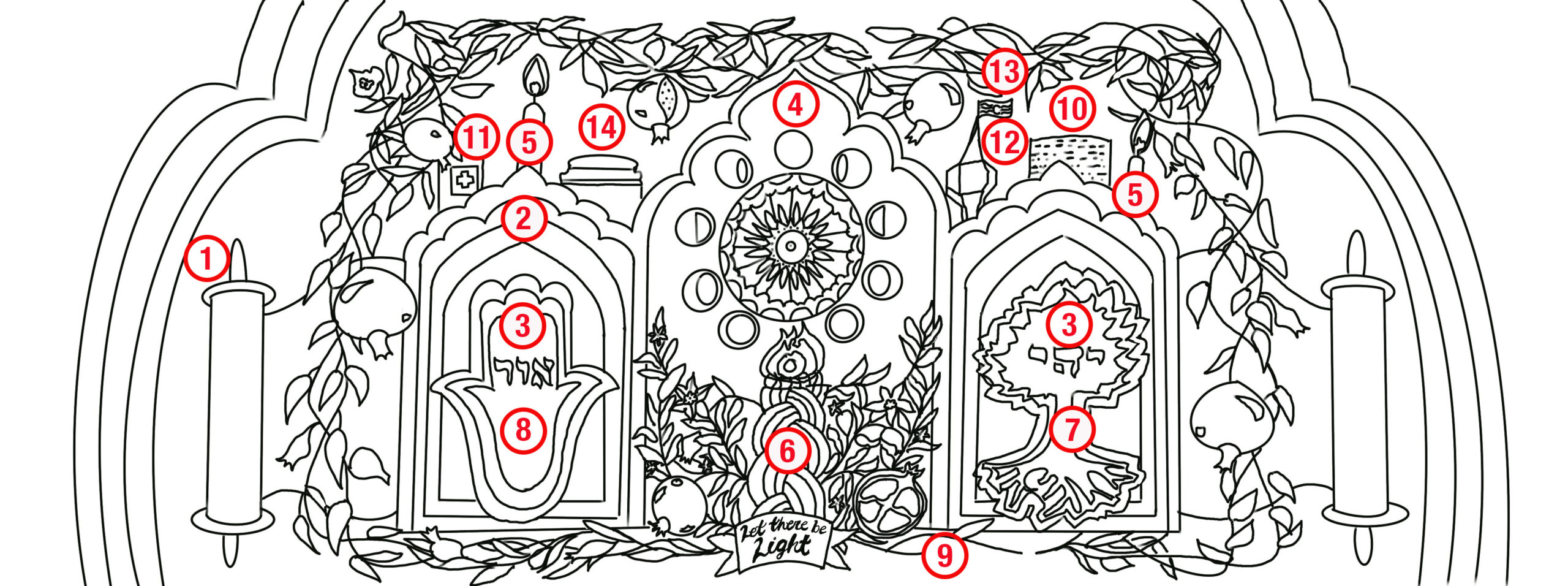

Jewish Symbols in the Mural Explained

- Torah Scroll

The entire mural is depicted as if placed on a Torah scroll, which, culturally, represents the heart and soul of the entire Jewish experience. A ritual object, the Torah scroll contains the Hebrew text of the Pentateuch, or the Five Books of Moses, handwritten on parchment rolled between two wooden staves. The Torah is the wellspring of Jewish history, and so it is fitting that the mural’s array of evocative Jewish images are floating on an unfurled Torah scroll. The mural memorializes the blessings of Jewish communal life in Cincinnati over the past two hundred years (1824-2024). The ancient rabbis believed the words of the Torah were as sweet as honey, and the images on this bicentennial mural remind us of the sweetness of Cincinnati’s Jewish heritage.

- Ketubah – Marriage Contract

The mural’s focal point features three large folios or frames with dome-shaped arches on the upper borders. Each one of these three “parchments” represents a ketubah, a typically beautifully adorned document on which is written the marital obligations that bind a couple together. Countless ketubot (pl. in Hebrew) have been signed in Cincinnati over the past two hundred years, reminding us of the many loving unions sanctified in accordance with Jewish tradition. These three ketubot contain winsome imagery that speak to the character and ideals of Jewish life in the Queen City of the West.

The distinctive arches are reminiscent of the façade of the Krohn Conservatory – Cincinnati’s magnificent botanical gardens. With over 3,500 plant species from around the world, Krohn Conservatory is one of the largest public greenhouses in the US, and is frequently referred to as “Cincinnati’s Garden of Eden.”

In 1937, the Eden Park Greenhouse was renamed the Krohn Conservatory in honor of Irwin M. Krohn (1869-1948), who served on the Board of the Park Commissioners from 1912-1948. Krohn was a local businessman whose love for Cincinnati knew no bounds. In addition to his dedicated service on the Park Board, Krohn was also a member of the Board of the Cincinnati Zoological Society, the Zoning Board of Appeals, and the City Planning Commission. Cincinnati’s Jewish community took pride in a man that Cincinnati Mayor Albert D. Cash memorialized as our city’s most “unselfish public servant.”

- Hebrew Text

The two Hebrew words on this mural are read from right to left and pronounced “yehee or.” This famous phrase comes from the third verse of the Book of Genesis: Let there be light! Like other religious traditions, Judaism insists that light is the primary link between the Divine and the human world. According to Jewish tradition, the soul of every human being contains a portion of the Divine light.

Like many of his contemporaries, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise (1819-1900), the renowned Cincinnati rabbi who founded the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, and Hebrew Union College, understood the phrase “Let there be light!” to be a clarion call for the pursuit of learning. Wise chose these very words as the masthead of the newspaper he founded in 1854, the American Israelite, which is today North America’s oldest Anglo-Jewish periodical in continuous publication. Wise believed that the ongoing pursuit of knowledge would bring more light into the world, and this light that would drive out the darkness of bigotry and hate. The mural calls out to all to affirm the conviction that a world enlightened by wisdom and ethics will create a brighter world for us and our posterity.

- The Lunar Cycle

The center of the mural depicts the evolving lunar cycle encircling a large, sun-like muqarnas dome from Cincinnati’s world-famous Plum Street Temple, dedicated in 1866 and still in use today. Stars and planets float in the background. These celestial images remind us that the Jewish people rely on a luni-solar calendar, where time is measured by the phases of the moon’s appearance and by the rising and the setting of the sun. These images suggest life’s cyclical nature. As the seasons turn, we should be mindful of the past, the present, and the inscrutable future. Finally, the Hebrew word for “star” is mazal, which evokes the well-known salutation: mazal tov!— “good luck!” The Jewish community wishes its friends and neighbors a heartfelt mazal tov! as it marks its 200th anniversary.

- The Sabbath and Shabbat Candles

Sabbath comes from the Hebrew word Shavat meaning “cease” or “desist.” Every Friday night through Saturday evening, Jews observe a period of rest—a sanctuary in time that breaks from the everyday practices of the work week. Every Jew honors the Sabbath (Shabbat in Hebrew) differently. Some abstain from all work, internet, screens, and the use of cars or electricity. Some observe by having a family meal on Friday night or Saturday afternoon. Some attend synagogue for worship. Learn more about Sabbath basics here, or check out this video and book 24/6 from Tiffany Shlain on the positive effects of weekly no-tech Sabbaths for all people, or dig into the deep philosophy of Jewish Sabbath theory with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel’s book, The Sabbath.

According to Jewish tradition, the Sabbath is welcomed with light. We welcome the Sabbath by lighting two candles, for the two different ways that the Biblical Ten Commandments refer to the Sabbath. The first such verse appears in the declamation of the Ten Commandments in the Book of Exodus (20:8), which states “Remember (zakhor) the Sabbath Day and sanctify it.” A second rendition of this same commandment appears in the Book of Deuteronomy (5:12): “Observe (shamor) the Sabbath Day and sanctify it.” You may learn more about Sabbath candle practices in Judaism here. Many Jewish people have a set of Sabbath candlesticks that pass from generation to generation, honoring light, memory, and practices across the generations.

- Havdalah

The Hebrew word havdalah means “a separation” or “a distinction.” Jews call the short ceremony that separates or distinguishes the Sabbath Day from the six days of the week the Havdalah ceremony. This lovely ritual makes use of some of the symbols used to welcome the Sabbath, but now they serve to awaken our senses to the opportunities awaiting us in the new week. The Havdalah ritual includes a sip of wine (taste), spices (smell), and a braided candle (sight or awareness). The Havdalah candle is itself distinctive with its many intertwined wicks. During the ritual, the Havdalah candle is customarily raised up high, and often people will lift their hands to watch the light flicker against their skin. This act reminds us that we can bring light and brightness into the world with our own hands. According to the Jewish mystical tradition, in the world to come, our skin will be made of light, shining from all the good deeds we performed over the course of our lifetimes.

- Tree of Life

The Tree of Life (in Hebrew, Etz Chayim) is mentioned ten times in the Hebrew Scriptures. In some of these passages, the phrase “Tree of Life” appears as a positive contrast to sickness and discouragement. In other verses, the Tree of Life is clearly an allusion to the knowledge and sacred wisdom that comes from the study of Torah. Perhaps the best-known reference to the Tree of Life as a symbol of Torah comes from the Book of Proverbs (3:18): [Torah is] “a tree of life to those who grasp it, and whoever holds on to it is happy.” Jewish folk tradition insists that the scroll itself brings people blessings and protects them from harm. It is for this reason that many Jewish congregations have chosen to call themselves Etz Chayim—a Tree of Life.

- Hamsa

The Hamsa, also known as the hand of Fatima or the hand of Miriam, is a symbol throughout Northern Africa and the Middle East. In many Middle Eastern cultures, it is an amulet for well-being, found in homes and jewelry. The open hand signifies protection from malice, illness, and misfortune. The Hamsa is a ubiquitous and ancient symbol embraced by Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, Pagans, and Jews alike.

- Pomegranates

Pomegranates are featured prominently in Jewish art, Biblical texts, stories, and in the Song of Songs (Cantillations), symbolizing righteousness, love, and fertility. Several folk practices involve pomegranates, including eating them on the Jewish New Year, one seed at a time, to fulfill as many wishes as possible; or claiming there are 613 seeds, the exact number of Jewish Biblical commandments. As one of Israel’s “seven species” and native to the Land of Israel, pomegranates, according to the Bible, were used to adorn priestly clothing and, also, the pillars of the sacred Temple. Over the generations, the pomegranate and the ideals it symbolizes have become familiar ornamentation in Jewish art and jewelry.

- Manischewitz Matzah

For millennia, matzah—unleavened bread—has been the focal point of Jewish ritual meals. The rise of machine-made matzah in the nineteenth century sparked a vigorous debate among Jewish legal authorities, many of whom insisted that machine-made matzah was not kosher. In 1888, Rabbi Dov Behr Manischewitz (1857-1914), an immigrant from Lithuania, started a small kosher bakery in Cincinnati’s Price Hill neighborhood where he automated the baking process and produced square-shaped matzah that was mass-marketed and shipped worldwide. Manischewitz managed to acquire rabbinical endorsements assuring the public that Manischewitz’ s machine-made matzah was as kosher as hand-made matzah. Over time, Manischewitz’ s matzah—sometimes called “Cincinnati matzah”—became the largest matzah manufacturer in the world. In his definitive article, “How Matzah Became Square: Manischewitz and the Development of Machine-Made Matzah in the United States,” Dr. Jonathan Sarna explores not only the industrial innovations that made square machine-made matzah normative, but also how business, politics, philanthropy, ties to Israel, and an ongoing commitment to Jewish law and Jewish life played a role in the remarkable story of Manischewitz matzah.

- Polio Vaccine/Jewish Hospital

By 1849, the Jewish community of Cincinnati had established a Jewish hospital, the first of its kind in the United States. It occupied two buildings at Betts and Cutter Streets in the West End before moving to Third and Baum Streets and eventually to Burnet Avenue and ultimately to Kenwood. Cincinnati’s Jewish Hospital was founded after the city’s cholera outbreak exposed the need for a place to treat indigent Jews, to better serve the health needs of Cincinnati Jewry, and to provide Jewish doctors with an opportunity to become hospital staff physicians.

One of the world’s greatest medical breakthroughs happened at the University of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation, where Dr. Albert Sabin (1906-1996) a Polish-Jewish immigrant, developed the oral polio vaccine. The war against polio that he began in 1931 ended in 1957 when the vaccine he had developed reached the point of mass administration, thus eliminating the disease in many parts of the world.

- Spice Box/Frank’s Hot Sauce

The elegant spice box depicted in the mural is one of the ritual objects used during the Havdalah Service (see Havdalah, above). The aromatic scent that comes from the spice box, typically filled with cinnamon, nutmeg, and clove, serves as a reminder of the pleasantness of the Sabbath as well as the hope that the new week that has begun will be sweet.

The spice box in this mural also reminds us of the Cincinnati origins of Frank’s RedHot Original Cayenne Pepper Sauce. In 1896, Jacob Frank (1867-1941) ended his career as a traveling salesman and went into business with his brothers Charles and Emil, establishing a company selling whole and ground spices, not in bulk, but in small, shelf-sized packages. Frank’s RedHot was born and bottled in the Queen City, produced by the Frank Tea and Spice Co., and first put on shelves in 1920.

- City Manager Form of Government/Murray Seasongood

The Cincinnati city flag atop the spice box symbolizes the long history of Cincinnati Jews as political leaders and public servants. One of Cincinnati’s six Jewish mayors was Murray Seasongood (1878-1983), who founded the Charter party while a councilman in 1924. Seasongood played a leading role in the Good Government Movement of the 1920s, which culminated in the passage of a new city charter in 1924 and the adoption of a city manager form of government. From 1926 to 1930, Seasongood served as the city’s mayor. Mayor Seasongood also championed the establishment of a regional park district. The Hamilton County Regional Park District (now the Great Parks of Hamilton County) was created during his term in office. Seasongood is also credited for having dismantled the powerful political machine run by George B. Cox (Boss Cox), and for much of his distinguished career he devoted himself to fighting corruption in city politics.

- Fleischmann’s Yeast

The familiar brown jar with a red and yellow label represents the story of Fleischmann’s Yeast, and how it revolutionized modern American baking. In 1868, Charles and Maximilian Fleischmann left Austria-Hungary to make a better life in America. After settling in Cincinnati, the Fleischmann brothers began their quest to make a better-rising bread like they had known in their homeland. In partnership with American businessman James Gaff, the Fleischmanns built a yeast plant in Cincinnati, where they produced and patented a compressed yeast cake that revolutionized home and commercial baking in the United States. It was America’s first commercially produced yeast, and soon became the country’s best-selling yeast and a household name.

Charles’s son, Julius Fleischmann (1871-1925), became Cincinnati’s youngest mayor in 1900. The 28-year-old Julius promoted universal education, a system of public parks, and the development of local railroad lines.

Senior Director, Impact: Sydney Fine

Lead Teaching Artists: Hannah Parrett and Kenton Brett

Teaching Artist: Monte Jones

Nico Breen

Twon Brown

Joseph Deters

Kelsey Gallagher

Sheridan Hennessey

Mira McKinney

Angela Ramirez

Lena Richards

Marlon Rudolph

Lexi Theurling

Vivien

Sam

Caitlin

Sloane

The Jewish Cincinnati Bicentennial

The Greater Cincinnati Foundation

Creative Ohio

ArtsWave

The Johnson Foundation